Week 1 Contextual Studies.

We looked at artists such as Piet Mondrian and Gerrit Reitveld and the influence they have over modern art, packaging and products. The size of the artists work makes a big difference on the impact that the image has on the viewer. Some artists made pieces 14ft wide to draw you in to make you feel like you are part of the scene. Michelangelo painted a fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine chapel, so the viewer had to look up as though looking to the heavens.

Piet Mondrian.

He was an important contributor to the De Stijl art movement and group, which was founded by Theo van Doesburg. He evolved a non-representational form which he termed neoplasticism

. This consisted of white ground, upon which wa

Mondrian was born in Amersfoort in the Netherlands, the second of his parents' children. He was descended from Christian Dirkzoon Monderyan who lived in The Hague as early as 1670. The family moved to Winterswijk in the east of the country, when his father, Pieter Cornelius Mondriaan, was appointed Head Teacher at a local primary school. Mondrian was introduced to art from a very early age: his father was a qualified drawing teacher; and, with his uncle, Fritz Mondriaan (a pupil of Willem Maris of the Hague School of artists), the younger Piet often painted and drew along the river Gein.

After a strictly Protestant upbringing, in 1892, Mondrian entered the Academy for Fine Art in Amsterdam. He already was qualified as a teacher. He began his career as a teacher in Primary Education, but he also practiced painting. Most of his work from this period is Naturalistic or Impressionistic, consisting largely of landscapes. These Pastoral images of his native country depict windmills, fields, and rivers, initially in the Dutch Impressionist manner of the Hague School and then in a variety of styles and techniques documenting his search for a personal style. These paintings are most definitely Representational, illustrating the influence various artistic movements had on Mondrian, including Pointillism and the vivid colors of Fauvism.

On display in the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague are a number of paintings from this period, including such Post-Impressionist works as The Red Mill and Trees in Moonrise. Another painting, Evening (Avond) (1908), a scene of haystacks in a field at dusk, even augurs future developments by using a palette consisting almost entirely of red, yellow, and blue. Although it is in no sense Abstract, Avond is the earliest of Mondrian's works to emphasize the primary colours.

Piet Mondrian, View from the Dunes with Beach and Piers, Domburg, oil and pencil on cardboard, 1909, Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Mondrian's art always was intimately related to his spiritual and philosophical studies. In 1908, he became interested in the theosophical movement launched by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky in the late 19th century; and, in 1909, he joined the Dutch branch of the Theosophical Society. The work of Blavatsky and a parallel spiritual movement, Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy, significantly affected the further development of his aesthetic. Blavatsky believed that it was possible to attain a more profound knowledge of nature than that provided by empirical means, and much of Mondrian's work for the rest of his life was inspired by his search for that spiritual knowledge.

Mondrian and his later work were deeply influenced by the 1911 Moderne Kunstkring exhibition of Cubism in Amsterdam. His search for simplification is shown in two versions of Still Life with Ginger Pot (Stilleven met Gemberpot). The 1911 version is Cubist; in, the 1912 version,it is reduced to a round shape with triangles and rectangles.s painted a grid of vertical and horizontal black lines and the three primary colours.

Gerrit Reitveld

Rietveld had taught himself drawing, painting and model-making. He afterwards set up in business as a cabinet-maker.

Rietveld designed his famous Red and Blue Chair in 1917. Hoping that much of his furniture would eventually be mass-produced rather than handcrafted, Rietveld aimed for simplicity in construction. In 1918, he started his own furniture factory, and changed the chair's colors after becoming influenced by the 'De Stijl' movement, of which he became a member in 1919, the same year in which he became an architect. The contacts that he made at De Stijl gave him the opportunity to exhibit abroad as well. In 1923, Walter Gropius invited Rietveld to exhibit at the Bauhaus. He designed his first building, the Rietveld Schröder House, in 1924, in close collaboration with the owner Truus Schröder-Schräder. Built in Utrecht on the Prins Hendriklaan 50, the house has a conventional ground floor, but is radical on the top floor, lacking fixed walls but instead relying on sliding walls to create and change living spaces. The design seems like a three-dimensional realization of a Mondrian painting. The house has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000. His involvement in the Schröder House exerted a strong influence on Truus' daughter, Han Schröder, who became one of the first female architects in the Netherlands.

Rietveld broke with 'De Stijl' in 1928 and became associated with a more functionalist style of architecture, known as either Nieuwe Zakelijkheid or Nieuwe Bouwen. The same year he joined the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne. From the late 1920s he was concerned with social housing, inexpensive production methods, new materials, prefabrication and standardisation. In 1927 he was already experimenting with prefabricated concrete slabs, a very unusual material at that time. In the 1920s and 1930s, however, all his commissions came from private individuals, and it was not until the 1950s that he was able to put his progressive ideas about social housing into practice, in projects in Utrecht and Reeuwijk.

Rietveld designed the Zig-Zag Chair in 1934 and started the design of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which was finished after his death.

Week 2 Contextual Studies.

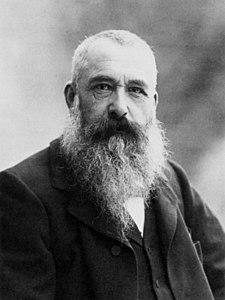

The birth of modern art. Claude Monets work shocked art lovers and critics around the world as it was not seen as the norm. His impressionistic style was seen to be lazy and not a true representation of the scene depicted, when in fact it was his interpretation of what he saw.Claude Monet The Water Lilly 1900 Claude Monet 1840-1926

Photo taken by Nadar 1899

When Monet traveled to Paris to visit the Louvre, he witnessed painters copying from the old masters. Having brought his paints and other tools with him, he would instead go and sit by a window and paint what he saw. Monet was in Paris for several years and met other young painters who would become friends and fellow impressionists; among them was Édouard Manet.

In June 1861, Monet joined the First Regiment of African Light Cavalry in Algeria for a seven-year commitment, but, two years later, after he had contracted typhoid fever, his aunt intervened to get him out of the army if he agreed to complete an art course at an art school. It is possible that the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind, whom Monet knew, may have prompted his aunt on this matter. Disillusioned with the traditional art taught at art schools, in 1862 Monet became a student of Charles Gleyre in Paris, where he met Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille and Alfred Sisley. Together they shared new approaches to art, painting the effects of light en plein air with broken color and rapid brushstrokes, in what later came to be known as Impressionism.

Monet's Camille or The Woman in the Green Dress (La femme à la robe verte), painted in 1866, brought him recognition and was one of many works featuring his future wife, Camille Doncieux; she was the model for the figures in Women in the Garden of the following year, as well as for On the Bank of the Seine, Bennecourt, 1868

Gustave Courbet

Courbet was a realist chooseing to paint pictures about peasent road workers, real people rather that aristocracy and gods, which shocked people.

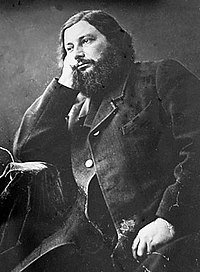

1819-1877 Self portrait 1843-45

Photo by Nadar

The stone breakers 1849 Good morning Mr Courbet 1854

In the Salon of 1857 Courbet showed six paintings. These included the scandalous Young Ladies on the Banks of the Seine (Summer), depicting two prostitutes under a tree, as well as the first of many hunting scenes Courbet was to paint during the remainder of his life: Hind at Bay in the Snow and The Quarry. By exhibiting sensational works alongside hunting scenes, of the sort that had brought popular success to the English painter Edwin Landseer, Courbet guaranteed himself "both notoriety and sales". During the 1860s, Courbet painted a series of increasingly erotic works such as Femme nue couchée. This culminated in The Origin of the World (L'Origine du monde) (1866), which depicts female genitalia and was not publicly exhibited until 1988, and Sleep (1866), featuring two women in bed. The latter painting became the subject of a police report when it was exhibited by a picture dealer in 1872.

By the 1870s, Courbet had become well established as one of the leading artists in France. On 14 April 1870, Courbet established a "Federation of Artists" (Fédération des artistes) for the free and uncensored expansion of art. The group's members included André Gill, Honoré Daumier, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Eugène Pottier, Jules Dalou, and Édouard Manet.

Paul Cezanne. 1839-1906

Cezanne painted from multiple view points and was the start of cubism.

In Paris, Cézanne met the Impressionist Camille Pissarro. Initially the friendship formed in the mid-1860s between Pissarro and Cézanne was that of master and disciple, in which Pissarro exerted a formative influence on the younger artist. Over the course of the following decade their landscape painting excursions together, in Louveciennes and Pontoise, led to a collaborative working relationship between equals.

Cézanne's early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape and includes many paintings of groups of large, heavy figures in the landscape, imaginatively painted. Later in his career, he became more interested in working from direct observation and gradually developed a light, airy painting style. Nevertheless, in Cézanne's mature work there is the development of a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. Throughout his life he struggled to develop an authentic observation of the seen world by the most accurate method of representing it in paint that he could find. To this end, he structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and colour planes. His statement "I want to make of impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums", and his contention that he was recreating Poussin "after nature" underscored his desire to unite observation of nature with the permanence of classical composition.

Week 3 Contextual Studies.

High Modernism.A new purpose for art.

This week we looked at a painting by William Holman Hunt called The Awakening Conscience, 1853/4 and compared it to a painting by Henri Matisse called The Green Line, 1905 A portrait of Madame Matisse

The Awakening Conscience has more detail the colours are more vibrant and rich, its more realistic, there's a sense of space and depth, perspective. It represents a frozen moment of a story. Its the point where she realises its time to get out of a sexual situation the moment when her conscious awakens.

The Green Line is a modernistic, semi realistic, semi figurative, semi abstract, cropped painting to put the focus on the subject. He used block colours and rough brush strokes not worrying about details to much, its almost cartoonistic with subjective use of colour. At the time when this was painted there were very strong Japanese influence's in France.

We then went on to look at Piet Mondrian's Composition, 1921

Week 4

Modernism & the modern world

In 1913 French writer Peguy wrote.... the world has changed less since the time of Jesus Christ than it has in the last thirty years.

What kind of changes was he referring to?

Photography changed the way artists painted. There was no need to paint exact replicas because a camera could do that much quicker, easier and more precisely.

This is what inspired artists to think outside the box and come up with new forms of art such as Cubism, futurism, fauvism, surrealism and realism.

The invention of photography.

The coining of the word "Photography" has been attributed in 1839 to Sir John Herschel based on the Greek φῶς (phos), (genitive: phōtós) meaning "light", and γραφή (graphê), meaning "drawing, writing", together meaning "drawing with light".

The history of photography commenced with the invention and development of the camera and the creation of permanent images starting with Thomas Wedgwood in 1790 and culminating in the work of the French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826.

View from the window is a 10 hour exposure.

Photographer Felix Nadar was the first person to photograph Paris from the air in a hot air balloon in 1858.

Industrealisation.

The first transformation to an industrial economy from an agricultural one, known as the Industrial Revolution, took place from the mid-18th to early 19th century in certain areas in Europe and North America; starting in Great Britain, followed by Belgium, Germany, and France. Later commentators have called this the first industrial revolution

The design of the Eiffel Tower was originated by Maurice Koechlin and Émile Nouguier, two senior engineers who worked for the Compagnie des Etablissements Eiffel after discussion about a suitable centrepiece for the proposed 1889 Exposition Universelle, a World's Fair which would celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution.

"not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the eighteenth century and by the Revolution of 1789, to which this monument will be built as an expression of France's gratitude."

The Eiffel Tower under construction.

After the exhibition, the building was rebuilt in an enlarged form on Penge Common next to Sydenham Hill, an affluent South London suburb full of large villas. It stood there from 1854 until its destruction by fire in 1936.

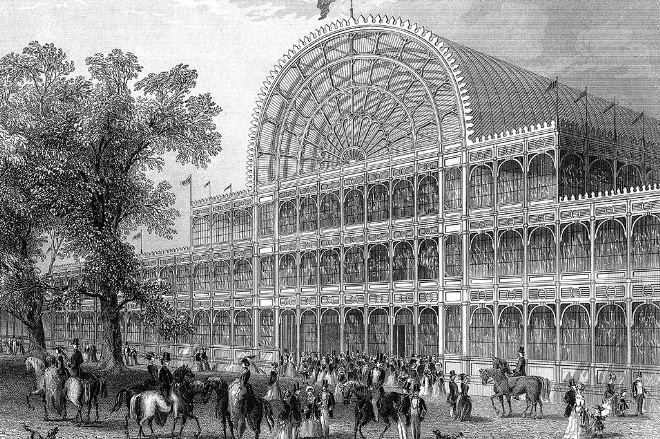

Rebuilding The Crystal Palace.

Inside The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace burnt down.

The Great Exhibition was opened on 1 May 1851 by Queen Victoria. It was the first of the World's Fair exhibitions of culture and industry. There were some 100,000 objects, displayed along more than ten miles, by over 15,000 contributors. Britain occupied half the display space inside with exhibits from the home country and the Empire. France was the largest foreign contributor. The exhibits were grouped into four main categories—Raw Materials, Machinery, Manufacturers and Fine Arts. The exhibits ranged from the Koh-i-Noor diamond, Sevres porcelain and music organs to a massive hydraulic press and a fire-engine. There was also a 27-foot tall Crystal Fountain.

At first the price of admission was £3 for gentlemen, £2 for ladies, later the masses were let in for only a shilling a head. Six million people—equivalent to a third of the entire population of Britain at the time—visited the Great Exhibition. The event made a surplus of £186,000 (£17,240,000 as of 2013), money which was used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum in South Kensington.

The Crystal Palace had the first major installation of public toilets, the Retiring Rooms, in which sanitary engineer George Jennings installed his "Monkey Closet" flushing lavatory (initially just for men, but later catering for women also). During the exhibition, 827,280 visitors each paid one penny to use them (from which originated the euphemism "spending a penny").

The Great Exhibition closed on 11 October 1851.

The Rock Drill 1913/14 Jacob Epstein

Writing about the piece in his autobiography Epstein said: “I made and mounted a machine-like robot, visored, menacing, and carrying within itself its progeny, protectively ensconced. Here is the armed, sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into…”

Metropolis is a 1927 German expressionist epic science-fiction film directed by Fritz Lang. The film was written by Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou, and starred Brigitte Helm, Gustav Fröhlich, Alfred Abel and Rudolf Klein-Rogge. A silent film, it was produced in the Babelsberg Studios by UFA.

Metropolis is regarded as a pioneer work of science fiction movies, being the first feature length movie of the genre.

Made in Germany during the Weimar Period, Metropolis is set in a futuristic urban dystopia, and follows the attempts of Freder, the wealthy son of the city's ruler, and Maria, whose background is not fully explained in the film, to overcome the vast gulf separating the classist nature of their city. Metropolis was filmed in 1925, at a cost of approximately five million Reichsmarks. Thus, it was the most expensive film ever released up to that point.

The film was met with a mixed response upon its initial release, with many critics praising its technical achievements and allegorical social metaphors with some deriding its "simplistic and naïve" presentation. Due both to its long running-time and footage censors found questionable, Metropolis was cut substantially after its German premiere; large portions of the film were lost over the subsequent decades.

Umberto Botccioni.

Dynamism of a cyclist 1913Umberto Boccioni.

Blurred and animated to give it the feeling of movement, speed and sound.

His paintings and sculptures embodided the Futurist concept of depicting a scenes energy through time, space and movement.

Eadweard Muybridge

In 1872, the former governor of California Leland Stanford, a businessman and race-horse owner, hired Muybridge for some photographic studies. He had taken a position on a popularly debated question of the day — whether all four feet of a horse were off the ground at the same time while trotting. The same question had arisen about the actions of horses during a gallop. The human eye could not break down the action at the quick gaits of the trot and gallop. Up until this time, most artists painted horses at a trot with one foot always on the ground; and at a full gallop with the front legs extended forward and the hind legs extended to the rear, and all feet off the ground. Stanford sided with the assertion of "unsupported transit" in the trot and gallop, and decided to have it proven scientifically. Stanford sought out Muybridge and hired him to settle the question.

In 1872, Muybridge settled Stanford's question with a single photographic negative showing his Standardbred trotting horse Occident airborne at the trot.

Week 5

Subject matter & Content

Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism and Surrealism.

Fauvism.

The word fauve is French for "wild beast" A loose group of early twentieth-century modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong colour over the representational or realistic values retained by impressionism. While Fauvism as a style began around 1900 and continued beyond 1910, the movement as such lasted only a few years, 1904–1908, and had three exhibitions. The leaders of the group were Henri Matisse and Andre Derain.

Above is a portrait of Henri Matisse by Andre Derain.

He used strong, bold, vivid colour's basic loose brush strokes with a traditional subject matter.

The image has been reduced to the basic essence of the human face. The detail is basic and nothing that doesn't need to be included has been left out.

Matisse says that destructive detail is harmful to the overall picture and that subject matter is secondary, art is an experience.

Cubism

An early 20th-century style and movement in art, especially

painting, in which perspective with a single viewpoint was abandoned and

use was made of simple geometric shapes, interlocking planes, and,

later, collage.

Above is violin & jug by George Braque.

He used a limited colour pallet and fragmented forms to make your eyes wonder around the whole image rather than focusing on a particular point or colour. Cubism works from multiple view points and geometric objects which are usually everyday objects such as jugs and musical instruments. It looks like this style of painting is an attempt at 3D. It is cognitive making your mind work to workout what it is your looking at to see what else is in the image.

Many of the artists associated with Cubism were influenced by African art and there masks and collected such art.

The match seller (1920) Otto Dix.

The match seller is a war veteran whose lost his legs and has been reduced to being a social leper with the more well to do walking away and the dog peeing on him.

Many of the artists associated with Cubism were influenced by African art and there masks and collected such art.

Expressionism (New Objectivity)

A style of painting, music, or drama in which the artist or writer seeks to express the inner world of emotion rather than external reality.

The match seller (1920) Otto Dix.

The match seller is a war veteran whose lost his legs and has been reduced to being a social leper with the more well to do walking away and the dog peeing on him.

Week 7

Modernist Aesthetics

Clive Bell

Arthur Clive Heward Bell (16 September 1881 – 18 September 1964), generally known as Clive Bell, was an English Art critic, associated with formalism and the Bloomsbury Group.

Clive Bell was born in East Shefford, Berkshire, in 1881. He was the third of four children of William Heward Bell (1849–1927) and Hannah Taylor Cory (1850–1942), with an elder brother (Cory), an elder sister (Lorna Bell Acton), and a younger sister (Dorothy Bell Honey). His father was a civil engineer who built his fortune in the family coal mines in Wiltshire in England and Merthyr Tydfil in Wales, and the family was well off. They lived at Cleve House in Seend, near Melksham, Wiltshire, which was adorned with Squire Bell's many hunting trophies.

Formalist theories differ according to how the notion of 'form' is understood. For Kant, it meant roughly the shape of an object – colour was not an element in the form of an object. For Bell, by contrast, "the distinction between form and colour is an unreal one; you cannot conceive of a colourless space; neither can you conceive a formless relation of colours"(Bell p19). Bell famously coined the term 'significant form' to describe the distinctive type of "combination of lines and colours" which makes an object a work of art.

Bell was also a key proponent of the claim that the value of art lies in its ability to produce a distinctive aesthetic experience in the viewer. Bell called this experience "aesthetic emotion". He defined it as that experience which is aroused by significant form. He also suggested that the reason we experience aesthetic emotion in response to the significant form of a work of art was that we perceive that form as an expression of an experience the artist has. The artist's experience in turn, he suggested, was the experience of seeing ordinary objects in the world as pure form: the experience one has when one sees something not as a means to something else, but as an end in itself (Bell, 45).

Bell believed that ultimately the value of anything whatever lies only in its being a means to "good states of mind" (Bell, 83). Since he also believed that "there is no state of mind more excellent or more intense than the state of aesthetic contemplation" (Bell, 83) he believed that works of visual art were among the most valuable things there could be. Like many in the Bloomsbury group, Bell was heavily influenced in his account of value by the philosopher G.E. Moore.

The theory of "Significant form" as propounded by Clive Bell in 1914 was that:

"There must be some one quality without which a work of art cannot exist; possessing which, in the least degree, no work is altogether worthless. What is this quality? What quality is shared by all objects that provoke our aesthetic emotions? What quality is common to Sta. Sophia and the windows at Chartres, Mexican sculpture, a Persian bowl , Chinese carpets, Giotto 's frescoes at Padua, and the masterpieces of Poussin, Piero della Francesca, and Cezanne? Only one answer seems possible - significant form. In each, lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions. These relations and combinations of lines and colours, these aesthetically moving forms, I call "Significant Form"; and "Significant form" is the one quality common to all works of visual art."

Bell's theory has obvious philosophical connections to the aesthetics of Immanuel Kant, who also stressed the detachment of aesthetic appreciation from other sorts of interest we might have in an object. His views also have close affinities with the ethical intuitionism of his British contemporary, the philosopher G.E. Moore. Moore is famous for claiming, in Principia Ethica (Cambridge University Press, 1903) that goodness is a property that things have in themselves, and that we know things to be good by a kind of intuition: one simply contemplates an object or a state of affairs and recognises immediately and directly that it is good, in much the same way that one recognises that it is red. Bell agreed with Moore, and considered aesthetic value to be one of these intuited forms of goodness.

It is easy to see how Bell's aesthetic would enable him to defend abstract art. For him, the aesthetic value of a painting or sculpture has absolutely nothing to do with its success as a representation of something else. Vasari to the contrary notwithstanding, if the Renaissance masters are great, it is not because they were so good at imitating nature, but because of the formal properties of their work. Judged by this new standard, Bell found many highly praised masters from the Renaissance through Impressionism to be deficient. (That was his judgement in Art; in his later writings he showed more appreciation for these painters.)

Like the aesthetics of Kant, that of Bell has a certain initial appeal, and no doubt represents an insight. In discussing a work of art, does it not often seem appropriate to draw the conversation back to the aesthetic quality of the work, in distinction from its skillful technique, its romantic associations, or what have you? Nevertheless Bell's theory has not withstood criticism well. Among the difficulties it faces are its apparent circularity, a problem it shares with Moore's intuitionist ethics. The conceptual circle of aesthetic emotion, aesthetic quality, and significant form is so small that in the end, one cannot give reasons why a work is good. For a theory which means to claim that some works objectively have aesthetic value and others do not, this is a set-up for the tyranny of unjustified judgements by influential critics.

A second problem of Bell's view is its sharp separation between aesthetic and other emotions. Some writers have questioned whether there is any such thing as the "aesthetic emotion". Even if there is such an emotion, it seems obvious that the power and value of many works is tied into their communication of meaning, and that their formal properties are only part of the vocabulary they use to communicate this meaning. Bell's theory seems to leave symbolism out of account, and no view that does that can be an adequate aesthetic theory.

Nigel Warburton writes in "Philosophy: The Basics" (P122) about two criticisms of the significant form theory. The first objection is that the theory involves a circular argument:

"The argument for the significant form theory appears to be circular. It seems only to be saying that the aesthetic emotion is produced by an aesthetic-emotion-producing property about which nothing more can be said. This is like explaining how a sleeping tablet works by referring to its sleep-inducing property. It is a circular argument because that which is supposed to be explained is used in the explanation. However, some circular arguments can be informative; those which cannot are known as viciously circular. Defenders of the theory would argue that it is not viciously circular as it sheds light on why some people are better critics than others, namely because they have a better ability to detect significant form. It also justifies treating works of art from different cultures and ages as similar in many ways to present-day works of art."The second objection to the theory is that it cannot be refuted. If according to the theory those who experience the aesthetic emotion are deemed to be appreciative and sensitive critics and those who do not experience the aesthetic emotion are deemed to be inexperienced or insensitive critics then the theory cannot be refuted because both supportive and unsupportive observations are used as evidence for the existence of the aesthetic emotion.

"this is to assume what the theory is supposed to be proving: that there is indeed one aesthetic emotion and that it is produced by genuine works of art. The theory, then, appears irrefutable. And many philosophers believe that if a theory is logically impossible to refute because every possible observation would confirm it, then it is a meaningless theory."

And yet......it is immediately clear that this theory does have at least one enormous strength. It is an embracing, inclusive theory which, whether you fully support it or not, enables you to view, compare and appreciate the entire stock of world art objects over the ages from a known and positive point of view. This is no mean achievement and sets this theory apart from many others which offer their insights on a narrower front. Of course, the Significant form theory is open to the charge that it pays little attention to the ideas behind the work of art. It also pays little attention to subject matter and content. It does however retain that foundational quality of dealing with the identification of what is the unique common quality to all works of art and therefore succeeds in achieving a great deal.

Form however has been identified by many others as a key component of the artistic process. For example, in "The Necessity of Art, A Marxist Approach" Ernst Fischer wrote in 1959:

Form however has been identified by many others as a key component of the artistic process. For example, in "The Necessity of Art, A Marxist Approach" Ernst Fischer wrote in 1959:

"In order to be an artist it is necessary to seize, hold and transform experience into memory, memory into expression, material into form"

Week 8

Materials & Technology

Traditionally artists use materials such as marble, stone, plaster and bronze for sculpting, oil and water colour paints, tempera pigment, canvas, paper, wood and walls (fresco's) for painting.

Tempera, also known as egg tempera, is a permanent, fast-drying painting medium consisting of coloured pigment mixed with a water-soluble binder medium (usually a glutinous material such as egg yolk or some other size).

Tempera also refers to the paintings done in this medium. Tempera

paintings are very long lasting, and examples from the 1st centuries AD

still exist. Egg tempera was a primary method of painting until after

1500 when it was superseded by the invention of oil painting.

Artists started to use non art materials such as glass, leather, plastic, hair, electric lights basically anything they could get hold of.

Artists started to use non art materials such as glass, leather, plastic, hair, electric lights basically anything they could get hold of.

Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction", stood for "School of Building".

The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a "total" work of art in which all arts, including architecture, would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design. The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography.

The school existed in three German cities: Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The Nazi government claimed that it was a centre of communist intellectualism. Though the school was closed, the staff continued to spread its idealistic precepts as they left Germany and emigrated all over the world.

Josef Albers.

Albers was born into a Roman Catholic family of craftsmen in Bottrop, Westphalia, Germany. He worked from 1908 to 1913 as a schoolteacher in his home town. Albers trained as an art teacher at Königliche Kunstschule in Berlin, Germany, from 1913 to 1915. From 1916 to 1919 he began his work as a printmaker at the Kunstgewerbschule in Essen. In 1918 he received his first public commission, Rosa mystica ora pro nobis, a stained-glass window for a church in Essen. In 1919 he went to Munich, Germany, to study at the Königliche Bayerische Akademie der Bildenden Kunst, where he was a pupil of Max Doerner and Franz Stuck.Albers enrolled as a student in the preliminary course (Vorkurs) of Johannes Itten at the Weimar Bauhaus in 1920. Although Albers had studied painting, it was as a maker of stained glass that he joined the faculty of the Bauhaus in 1922, approaching his chosen medium as a component of architecture and as a stand-alone art form. The director and founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, asked him in 1923 to teach in the preliminary course ‘Werklehre' of the department of design to introduce newcomers to the principles of handicrafts, because Albers came from that background and had appropriate practice and knowledge.

In 1925, Albers was promoted to professor, the year the Bauhaus moved to Dessau. At this time, he married Anni Albers (née Fleischmann) who was a student there. His work in Dessau included designing furniture and working with glass. As a younger art teacher, he was teaching at the Bauhaus among artists who included Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee. The so-called form master, Klee taught the formal aspects in the glass workshops where Albers was the crafts master; they cooperated for several years.

With the closure of the Bauhaus under Nazi pressure in 1933 the artists dispersed, most leaving the country. Albers emigrated to the United States. The architect Philip Johnson, then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, arranged for Albers to be offered a job as head of a new art school, Black Mountain College, in North Carolina. In November 1933, he joined the faculty of the college where he was the head of the painting program until 1949.

Naum Gabo.

The essence of Gabo's art was the exploration of space, which he believed could be done without having to depict mass. His earliest constructions such as Head No.2 were formal experiments in depicting the volume of a figure without carrying its mass. Gabo's other concern as described in the Realist Manifesto was that art needed to exist actively in four dimensions including time.

Gabo's formative years were in Munich, where he was inspired by and actively participated in the artistic, scientific, and philosophical debates of the early years of the 20th century. Because of his involvement in these intellectual debates, Gabo became a leading figure in Moscow’s avant garde, in post-Revolution Russia. It was in Munich that Gabo attended the lectures of art historian Heinrich Wölfflin and gained knowledge of the ideas of Einstein and his fellow innovators of scientific theory, as well as the philosopher Henri Bergson. As a student of medicine, natural science and engineering, his understanding of the order present in the natural world mystically links all creation in the universe. Just before the onset of the First World War in 1914, Gabo discovered contemporary art, by reading Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which asserted the principles of abstract art.

Gabo’s vision is imaginative and passionate. Over the years his exhibitions have generated immense enthusiasm because of the emotional power present in his sculpture. Gabo described himself as “making images to communicate my feelings of the world.” In his work, Gabo used time and space as construction elements and in them solid matter unfolds and becomes beautifully surreal and otherworldly. His sculptures initiate a connection between what is tangible and intangible, between what is simplistic in its reality and the unlimited possibilities of intuitive imagination. Imaginative as Gabo was, his practicality lent itself to the conception and production of his works. He devised systems of construction which were not only used for his elegantly elaborate sculptures but were viable for architecture as well. He was also innovative in his works, using a wide variety of materials including the earliest plastics, fishing line, bronze, sheets of Perspex, and boulders. He sometimes even used motors to move the sculpture.

Caroline Collier, an authority on Gabo’s work, said, “The real stuff of Gabo’s art is not his physical materials, but his perception of space, time and movement. In the calmness at the ‘still centre’ of even his smallest works, we sense the vastness of space, the enormity of his conception, time as continuous growth.” In fact, the element of movement in Gabo’s sculpture is connected to a strong rhythm, more implicit and deeper than the chaotic patterns of life itself. The exactness of form leads the viewer to imagine journeying into, through, over and around his sculptures.

Gabo wrote his Realistic Manifesto, in which he ascribed his philosophy for his constructive art and his joy at the opportunities opened up by the Russian Revolution. Gabo saw the Revolution as the beginning of a renewal of human values. Five thousand copies of the manifesto tract were displayed in Moscow streets in 1920.

Gabo had lived through a revolution and two world wars; he was also Jewish and had fled Nazi Germany. Gabo’s acute awareness of turmoil sought out solace in the peacefulness that was so fully realized in his “ideal” art forms. It was in his sculpture that he evaded all the chaos, violence, and despair he had survived. Gabo chose to look past all that was dark in his life, creating sculptures that though fragile are balanced so as to give us a sense of the constructions delicately holding turmoil at bay.

Head No2 1916 enlarged version 1964.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy 1895-1946

Hungarian-born abstract painter, designer, typographer, photographer, film-maker and theorist. Born in Bácsborsód. Studied law at Budapest University. After serving in the Austro-Hungarian Army and being severely wounded, started to draw and in 1917 to paint. Moved to Berlin 1920-3. Began to paint abstract pictures in 1920 under the influence of Malevich and Lissitzky, and had his first one-man exhibition at the Galerie Der Sturm, Berlin, 1922. Met Gropius and was appointed in 1923 to the Bauhaus at Weimar, first as head of the metal workshop, then head of the preparatory course; moved with the Bauhaus to Dessau 1925. Became much involved with experimental photography, including photograms, and published Malerei, Fotographie, Film 1925. Made a 'Light-Space-Modulator' 1922-30. Resigned from the Bauhaus in 1928 and returned to Berlin, where he temporarily more or less gave up painting and made stage designs, abstract films and typographical works. Published Vom Materiel zur Architektur 1929. Moved to Amsterdam in 1934 and from 1935-7 lived in London, where he worked as art adviser to Simpson's and London Transport, and began to make paintings incorporating plastics. Moved in 1937 to Chicago, where he became director of the New Bauhaus and later opened his own School of Design. Died in Chicago.

K VII 1922

Perhaps his most enduring achievement is the construction of the "Lichtrequisit einer elektrischen Buehne" [Light Prop for an Electric Stage] (completed 1930), a device with moving parts meant to have light projected through it in order to create mobile light reflections and shadows on nearby surfaces. Made with the help of the Hungarian architect Istvan Seboek for the German Werkbund exhibition held in Paris during the summer of 1930, it is often interpreted as a kinetic sculpture. After his death, it was dubbed the "Light-Space Modulator" and was seen as a pioneer achievement of kinetic sculpture. It might more accurately be seen as one of the earliest examples of Light Art. Moholy-Nagy was photography editor of the Dutch avant-garde magazine International Revue i 10 from 1927 to 1929. He resigned from the Bauhaus early in 1928 and worked free-lance as a highly sought-after designer in Berlin. He designed stage sets for successful and controversial operatic and theatrical productions, designed exhibitions and books, created ad campaigns, wrote articles and made films. His studio employed artists and designers such as Istvan Seboek, Gyorgy Kepes and Andor Weininger. After the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, and, as a foreign citizen, he was no longer allowed to work, he operated for a time in Holland (doing mostly commercial work) before moving to London in 1935.

In England, Moholy-Nagy formed part of the circle of émigré artists and intellectuals who based themselves in Hampstead. Moholy-Nagy lived for a time in the Isokon building with Walter Gropius for eight months and then settled in Golders Green. Gropius and Moholy-Nagy planned to establish an English version of the Bauhaus but could not secure backing, and then Moholy-Nagy was turned down for a teaching job at the Royal College of Art. Moholy-Nagy made his way in London by taking on various design jobs including Imperial Airways and a shop display for men's underwear. He photographed contemporary architecture for the Architectural Review where the assistant editor was John Betjeman who commissioned Moholy-Nagy to make documentary photographs to illustrate his book An Oxford University Chest. In 1936, he was commissioned by fellow Hungarian film producer Alexander Korda to design special effects for Things to Come. Working at Denham Studios, Moholy-Nagy created kinetic sculptures and abstract light effects, but they were rejected by the film's director. At the invitation of Leslie Martin, he gave a lecture to the architecture school of Hull University.

Light Space Modulator 1922-1930

Marcel Duchamp 1887-1968

Marcel Duchamp (French: [maʁsɛl dyʃɑ̃]; 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) was a French-American painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Dadaism and conceptual art, although not directly associated with Dada groups. Duchamp is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the three artists who helped to define the revolutionary developments in the plastic arts in the opening decades of the twentieth century, responsible for significant developments in painting and sculpture. Duchamp has had an immense impact on twentieth-century and twenty first-century art. By World War I, he had rejected the work of many of his fellow artists (like Henri Matisse) as "retinal" art, intended only to please the eye. Instead, Duchamp wanted to put art back in the service of the mind.

In 1958 Duchamp said of creativity,

The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.

The name of the piece, L.H.O.O.Q. (in French èl ache o o qu), is a pun, since the letters when pronounced in French form the sentence "Elle a chaud au cul", literally "She is hot in the arse". This phrase bears resemblance to "avoir chaud au cul", a vulgar expression directed at women implying sexual restlessness. This interpretation is supported by Duchamp in a late interview (Schwarz 203), where he gives a loose translation of L.H.O.O.Q. as "there is fire down below".

As was the case with a number of his readymades, Duchamp made multiple versions of L.H.O.O.Q. of differing sizes and in different media throughout his career, one of which, an unmodified black and white reproduction of the Mona Lisa mounted on card, is called L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved. The masculinized female introduces the theme of gender reversal, which was popular with Duchamp, who adopted his own female pseudonym, Rrose Sélavy, pronounced "Eros, c'est la vie" ("Eros, that's life").

Primary responses to L.H.O.O.Q. interpreted its meaning as being an attack on the iconic Mona Lisa and traditional art, thus promoting the Dadadist ideals.

According to Rhonda R. Shearer, the apparent reproduction is in fact a copy partly modelled on Duchamp's own face.

Marcel Duchamp Fountain 1917

Readymades

Readymades" were found objects which Duchamp chose and presented as art. In 1913, Duchamp installed a Bicycle Wheel in his studio. However, the idea of Readymades did not fully develop until 1915. The idea was to question the very notion of Art, and the adoration of art, which Duchamp found "unnecessary"

My idea was to choose an object that wouldn't attract me, either by its beauty or by its ugliness. To find a point of indifference in my looking at it, you see.

Bottle Rack (1914), a bottle drying rack signed by Duchamp, is considered to be the first "pure" readymade. Prelude to a Broken Arm (1915), a snow shovel, also called In Advance of the Broken Arm, followed soon after. His Fountain, a urinal signed with the pseudonym "R. Mutt", shocked the art world in 1917. Fountain was selected in 2004 as "the most influential artwork of the 20th century" by 500 renowned artists and historians.

In 1919, Duchamp made a parody of the Mona Lisa by adorning a cheap reproduction of the painting with a mustache and goatee. To this he added the inscription L.H.O.O.Q., a phonetic game which, when read out loud in French quickly sounds like "Elle a chaud au cul". This can be translated as "She has a hot ass", implying that the woman in the painting is in a state of sexual excitement and availability. It may also have been intended as a Freudian joke, referring to Leonardo da Vinci's alleged homosexuality. Duchamp gave a "loose" translation of L.H.O.O.Q. as "there is fire down below" in a late interview with Arturo Schwarz. According to Rhonda Roland Shearer, the apparent Mona Lisa reproduction is in fact a copy modeled partly on Duchamp's own face. Research published by Shearer also speculates that Duchamp himself may have created some of the objects which he claimed to be "found objects".

Duchamp worked on his complex Futurism inspired piece The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) from 1915 to 1923, with the exception of periods in Buenos Aires and Paris in 1918–1920. He executed the work on two panes of glass with materials such as lead foil, fuse wire, and dust. It combines chance procedures, plotted perspective studies, and laborious craftsmanship. He published notes for the piece, The Green Box, intended to complement the visual experience. They reflect the creation of unique rules of physics, and a mythology which describes the work. He stated that his "hilarious picture" is intended to depict the erotic encounter between a bride and her nine bachelors.

The piece was inspired by a performance of the stage adaptation of Roussel's novel Impressions d'Afrique which Duchamp attended in 1912. Notes, sketches and plans for the work were drawn on Duchamp's studio walls as early as 1913. In order to concentrate on the work free from material obligations, Duchamp found work as a librarian while living in France. After emigrating to the United States in 1915, he commenced his work on the piece financed by the support of the Arensbergs.

The piece is partially constructed as a retrospective of Duchamp's works, including a three dimensional reproduction of his earlier paintings Bride (1912), Chocolate Grinder (1914) and Glider containing a water mill in neighboring metals (1913–1915), which has opened for numerous interpretations. The work was formally declared "Unfinished" in 1923. Going home from its first public exhibition, the glass broke in its shipping crate and received a large crack in the glass. Duchamp repaired it, but left the cracks in the glass intact, accepting the chance element as a part of the piece.

Until 1969 when the Philadelphia Museum of Art revealed Duchamp's Étant donnés tableau, The Large Glass was thought to have been his last major work.

Duchamp's interest in kinetic works can be discerned as early as the notes for The Large Glass and the Bicycle Wheel readymade, and despite losing interest in "retinal art", he retained interest in visual phenomena. In 1920, with help from Man Ray, Duchamp built a motorized sculpture, Rotative plaques verre, optique de précision ("Rotary Glass Plates, Precision Optics"). The piece, which he did not consider to be art, involved a motor to spin pieces of rectangular glass on which were painted segments of a circle. When the apparatus spins, an optical illusion occurs, in which the segments appear to be closed concentric circles. Man Ray set up equipment to photograph the initial experiment, but when they turned the machine on for the second time, a belt broke, and caught a piece of the glass, which after glancing off Man Ray's head, shattered into bits.

After moving back to Paris in 1923, at André Breton's urging and through the financing of Jacques Doucet, Duchamp built another optical device based on the first one, Rotative Demisphère, optique de précision (Rotary Demisphere, Precision Optics). This time the optical element was a globe cut in half, with black concentric circles painted on it. When it spins, the circles appear to move backwards and forwards in space. Duchamp asked that Doucet not exhibit the apparatus as art.

Rotoreliefs were the next phase of Duchamp's spinning works. To make the optical "play toys", he painted designs on flat cardboard circles and spun them on a phonographic turntable. When spinning, the flat disks appeared three-dimensional. He had a printer produce 500 sets of six of the designs, and set up a booth at a 1935 Paris inventors' show to sell them. The venture was a financial disaster, but some optical scientists thought they might be of use in restoring three-dimensional stereoscopic sight to people who have lost vision in one eye. In collaboration with Man Ray and Marc Allégret, Duchamp filmed early versions of the Rotoreliefs and they named the film Anémic Cinéma (1926). Later, in Alexander Calder's studio in 1931, while looking at the sculptor's kinetic works, Duchamp suggested that these should be called "mobiles". Calder agreed to use this novel term in his upcoming show. To this day, sculptures of this type are called "mobiles".

Between 1912 and 1915, Duchamp worked with various musical ideas. At least three pieces have survived: two compositions and a note for a musical happening. The two compositions are based on chance operations. Erratum Musical, written for three voices, was published in 1934. La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même. Erratum Musical is unfinished and was never published or exhibited during Duchamp's lifetime. According to the manuscript, the piece was intended for a mechanical instrument "in which the virtuoso intermediary is suppressed". The manuscript also contains a description for "An apparatus automatically recording fragmented musical periods", consisting of a funnel, several open-end cars and a set of numbered balls. These pieces predate John Cage's Music of Changes (1951), which is often considered the first modern piece to be conceived largely through random procedures.

In 1968, Duchamp and John Cage appeared together at a concert entitled "Reunion", playing a game of chess and composing Aleatoric music by triggering a series of photoelectric cells underneath the chessboard.

DADA

Dada or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century. It began in Zurich, Switzerland in 1916, spreading to Berlin shortly thereafter. To quote Dona Budd's The Language of Art Knowledge, Dada was born out of negative reaction to the horrors of World War I. This international movement was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality and intuition. The origin of the name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsensical word. Others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco's frequent use of the words da, da, meaning yes, yes in the Romanian language. Another theory says that the name "Dada" came during a meeting of the group when a paper knife stuck into a French-German dictionary happened to point to 'dada', a French word for 'hobbyhorse'.

The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature, poetry, art manifestos, art theory, theatre, and graphic design, and concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works. In addition to being anti-war, Dada was also anti-bourgeois and had political affinities with the radical left.

Dada activities included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and culture were topics often discussed in a variety of media. Key figures in the movement included Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Johannes Baader, Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Richard Huelsenbeck, Georg Grosz, John Heartfield, Marcel Duchamp, Beatrice Wood, Kurt Schwitters, and Hans Richter, among others. The movement influenced later styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including surrealism, Nouveau réalisme, pop art and Fluxus.

Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of antiart to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that lay the foundation for Surrealism.

New York Dada had a less serious tone than that of European Dadaism, and was not a particularly organised venture. Duchamp's friend Francis Picabia connected with the Dada group in Zürich, bringing to New York the Dadaist ideas of absurdity and "anti-art". Duchamp and Picabia first met in September 1911 at the Salon d'Automne in Paris, where they were both exhibiting. Duchamp showed a larger version of his Young Man and Girl in Spring 1911, a work that had an Edenic theme and a thinly veiled sexuality also found in Picabia's contemporaneous Adam and Eve 1911. According to Duchamp, 'our friendship began right there". A group met almost nightly at the Arensberg home, or caroused in Greenwich Village. Together with Man Ray, Duchamp contributed his ideas and humour to the New York activities, many of which ran concurrent with the development of his Readymades and 'The Large Glass.'

The most prominent example of Duchamp's association with Dada was his submission of Fountain, a urinal, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibit in 1917. Artworks in the Independent Artists shows were not selected by jury, and all pieces submitted were displayed. However, the show committee insisted that Fountain was not art, and rejected it from the show. This caused an uproar amongst the Dadaists, and led Duchamp to resign from the board of the Independent Artists.

Along with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, Duchamp published a Dada magazine in New York, titled The Blind Man, which included art, literature, humour and commentary.When he returned to Paris after World War I, Duchamp did not participate in the Dada group.

Constantin Brancusi 1876-1957

Constantin Brâncuși (Romanian: [konstanˈtin brɨŋˈku; February 19, 1876 – March 16, 1957) was a Romanian-born sculptor who made his career in France. As a child he displayed an aptitude for carving wooden farm tools. Formal studies took him first to Bucharest, then to Munich, then to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His abstract style emphasises clean geometrical lines that balance forms inherent in his materials with the symbolic allusions of representational art. Famous Brâncuși works include the Sleeping Muse (1908), The Kiss (1908), Prometheus (1911), Mademoiselle Pogany (1913), The Newborn (1915), Bird in Space (1919) and The Column of the Infinite (Coloana infinitului), popularly known as The Endless Column (1938). Considered a pioneer of modernism, Brâncuși is called the patriarch of modern sculpture.

Portrait of Mlle Pogany 1912

Modernism in other disciplines.

The characteristics of and ideas behind modernist art are the relevance to the contempery age. Modern art is non narowtive, form becomes more important than subject matter. Materials become part of the meaning of the work, new materials, non art materials. The attitude to disciplines become more exaggerated, experimental, venturing into different disciplines.

A manifesto of Le Corbusier's "five points" of new architecture, the villa is representative of the bases of modern architecture, and is one of the most easily recognizable and renowned examples of the International style.

The house was originally built as a country retreat on behest of the Savoye family. During WWII the Jewish Savoye family was sent to concentration camps by the Nazis who took over the house and used it for storage. After being purchased by the neighbouring school it passed on to be property of the French state in 1958, and after surviving several plans of demolition, it was designated as an official French historical monument in 1965 (a rare occurrence, as Le Corbusier was still living at the time). It was thoroughly renovated from 1985 to 1997, and under the care of the Centre des monuments nationaux, the refurbished house is now open to visitors year-round.

Florence Henri

Florence Henri was born on the 28 June 1893, New York – 24 July 1982, Laboissière-en-Thelle) was a photographer and artist. She grew up in Europe and studied in Rome, where she met the futurists, and in Berlin, then in Paris with Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant, and finally at the Dessau Bauhaus before returning to Paris where she started with photography. Her work includes experimental photography, advertising, and portraits, many of artists.Villa Savoye

Villa Savoye (French pronunciation: [saˈvwa]) is a modernist villa in Poissy, in the outskirts of Paris, France. It was designed by Swiss architects Le Corbusier and his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, and built between 1928 and 1931 using reinforced concrete.A manifesto of Le Corbusier's "five points" of new architecture, the villa is representative of the bases of modern architecture, and is one of the most easily recognizable and renowned examples of the International style.

The house was originally built as a country retreat on behest of the Savoye family. During WWII the Jewish Savoye family was sent to concentration camps by the Nazis who took over the house and used it for storage. After being purchased by the neighbouring school it passed on to be property of the French state in 1958, and after surviving several plans of demolition, it was designated as an official French historical monument in 1965 (a rare occurrence, as Le Corbusier was still living at the time). It was thoroughly renovated from 1985 to 1997, and under the care of the Centre des monuments nationaux, the refurbished house is now open to visitors year-round.

Background

By the end of the 1920s Corbusier was already an internationally known architect. His book Vers une Architecture had been translated into several languages, his work with the Centrosoyuz in Moscow involved him with the Russian avant-garde and his problems with the League of Nations competition had been widely publicised. Also he was one of the first members of Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) and was becoming known as a champion of modern architecture.[7]

The villas designed by Corbusier in the early part of the 1920s

demonstrated what he termed the "precision" of architecture, where each

feature of the design needed to be justified in design and urban terms.

His work in the later part of the decade, including his designs urban

for Algiers began to be more free-form.[8] .

History of the commission

Pierre and Emilie Savoye approached Corbusier about building a

country home in Poissy in the spring of 1928. The site was on a green

field on an otherwise wooded plot of land with a magnificent landscape

view to the north west that corresponded with the approach to the site

along the road. Other than an initial brief prepared by Emile

for a summer house, space for cars, an extra bedroom and a caretaker's

lodge, Corbusier had such freedom with the job that he was only limited

by his own architectural palette. He began work on the project in

September 1928. His initial ideas were those that eventually manifested

themselves in the final building but between Autumn 1928 and Spring 1929

he undertook a series of alternatives that were influenced primarily by

the Savoye's concern about cost.

The eventual solution to this problem was to reduce the volume of the

building by moving the master bedroom down to the first floor and

reducing the grid spacing down from 5 metres to 4.75 metres.

Construction

Estimates of the cost in February 1929 were approximately half a million Francs,

although this excluded the cost of the lodge and the landscaping

elements (almost twice the original budget). The project was tendered in

February with contracts awarded in March 1929. Changes made to the

design whilst the project was being built including an amendment to the

storey height and the exclusion and then re-introduction of the

chauffeur's accommodation led to the costs rising to approximately

800,000 Francs. At the time the project started on site no design work

had been done on the lodge and the final design was only presented to

the client in June 1929. The design was for a double lodge but this was

reduced to a single lodge as the costs were too high. Although construction of the whole house was complete within a year it was not habitable until 1931.

Design

The Villa Savoye is probably Corbusier's best known building from the

1930s, it had enormous influence on international modernism. It was designed addressing his emblematic "Five Points", the basic tenets in his new architectural aesthetic:

- Support of ground-level pilotis, elevating the building from the earth and allowed an extended continuity of the garden beneath.

- Functional roof, serving as a garden and terrace, reclaiming for nature the land occupied by the building.

- Free floor plan, relieved of load-bearing walls, allowing walls to be placed freely and only where aesthetically needed.

- Long horizontal windows, providing illumination and ventilation.

- Freely-designed facades, serving only as a skin of the wall and windows and unconstrained by load-bearing considerations.

The plan was set out using the principal ratios of the Golden section: in this case a square divided into sixteen equal parts, extended on two sides to incorporate the projecting façades and then further divided to give the position of the ramp and the entrance.

In his book Vers une Architecture Corbusier exclaimed "the motor car is an object with a simple function (to travel) and complicated aims (comfort, resistance, appearance)...". The house, designed as a second residence and sited as it was outside Paris was designed with the car in mind. The sense of mobility that the car gave translated into a feeling of movement that is integral to the understanding of the building. The approach to the house was by car, past the caretaker's lodge and eventually under the building itself. Even the curved arc of the industrial glazing to the ground floor entrance was determined by the turning circle of a car. Dropped off by the chauffeur, the car proceeded around the curve to park in the garage. Meanwhile the occupants entered the house on axis into the main hall through a portico of flanking columns.

The four columns in the entrance hall seemingly direct the visitor up the ramp. This ramp, that can be seen from almost everywhere in the house continues up to the first floor living area and salon before continuing externally from the first floor roof terrace up to the second floor solarium. Throughout his career Corbusier was interested in bringing a feeling of sacredness into the act of dwelling and acts such as washing and eating were given significance by their positioning. At the Villa Savoye the act of cleansing is represented both by the sink in the entrance hall and the celebration of the health-giving properties of the sun in the solarium on the roof which is given significance by being the culmination of ascending the ramp.

Corbusier's piloti perform a number of functions around the house, both inside and out. On the two longer elevations they are flush with the face of the façade and imply heaviness and support, but on the shorter sides they are set back giving a floating effect that emphasises the horizontal feeling of the house. The wide strip window to the first floor terrace has two baby piloti to support and stiffen the wall above. Although these piloti are in a similar plane to the larger columns below a false perspective when viewed from outside the house gives the impression that they are further into the house than they actually are.

The Villa Savoye uses the horizontal ribbon windows found in his earlier villas. Unlike his contemporaries, Corbusier often chose to use timber windows rather than metal ones. It has been suggested that this is because he was interested in glass for its planar properties and that the set-back position of the glass in the timber frame allowed the façade to be seen as a series of parallel planes.

Later history

Problems with the Savoyes caused by all the requests for additional payment from the contractors for all the changes were compounded by the requirement for early repairs to the new house. Each autumn the Savoyes suffered problems with rainwater leaks through the roof. The Savoyes continued to live in the house until 1940, leaving during World War II. It was occupied twice during the war: first by the Germans - when it was used as a hay store - and then by the Americans, with both occupations damaging the building severely. The Savoyes returned to their estate after the war, but, no longer in position to live as they had done before the war, they abandoned the house again shortly after. The villa was expropriated by of the town of Poissy in 1958, which first used it as a public youth center and later considered demolishing it to make way for a schoolhouse complex. Protest from architects who felt the house should be saved, and the intervention of Corbusier himself, spared the house from demolition. A first attempt of renovation was begun in 1963 by architect Jean Debuisson, despite opposition from Corbusier. The villa was added to the French register of historical monuments in 1965, becoming the first modernist building designated as historical monument in France, and also the first to be the object of renovation while its architect was still living. In 1985, a thorough state-funded restoration process, led by architect Jean-Louis Véret, was undertaken, being completed in 1997. The restoration included structural and surface repairs to the facades and terraces because of deterioration of the concrete, the installation of lighting and security cameras, and the reinstatement of some of the original fixtures and fittings.Legacy

The freedom given to Corbusier by the Savoyes resulted in a house that was governed more by his five principles than any requirements of the occupants. Despite this, it was the last time this happened in such a complete way and the house marked the end of a phase in his design thinking as well as being the last of a series of buildings dominated by the colour white.

Criticism has been levelled at Corbusier's five points of architecture from a general point of view and these apply specifically to the Villa Savoye in terms of:

- Support of ground-level pilotis - the piloti tended to be symbolic rather than representative of actual structure.

- Functional roof - poor detailing in this case led to the roof leaking.

The west wing of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in Canberra designed by Ashton Raggatt McDougall, is a near exact replica of the Villa Savoye, except its black colour. This antipodean architectural quotation is according to Howard Raggat "a kind of inversion, a reflection, but also a kind of shadow".

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch (Norwegian: [ˈɛdvɑʈ muŋk] ; 12 December 1863 – 23 January 1944) was a Norwegian painter and printmaker whose intensely evocative treatment of psychological themes built upon some of the main tenets of late 19th-century Symbolism and greatly influenced German Expressionism in the early 20th century. One of his most well-known works is The Scream of 1893.

Childhood

Edvard Munch was born in a rustic farmhouse in the village of Ådalsbruk in Løten, Norway, to Laura Catherine Bjølstad and Christian Munch, the son of a priest. Christian was a doctor and medical officer who married Laura, a woman half his age, in 1861. Edvard had an elder sister, Johanne Sophie, and three younger siblings: Peter Andreas, Laura Catherine, and Inger Marie. Both Sophie and Edvard appear to have inherited their artistic talent from their mother. Edvard Munch was related to painter Jacob Munch and historian Peter Andreas Munch.

The family moved to Christiania (now Oslo) in 1864 when Christian Munch was appointed medical officer at Akershus Fortress. Edvard's mother died of tuberculosis in 1868, as did Munch's favorite sister Johanne Sophie in 1877. After their mother's death, the Munch siblings were raised by their father and by their aunt Karen. Often ill for much of the winters and kept out of school, Edvard would draw to keep himself occupied, and received tutoring from his school mates and his aunt. Christian Munch also instructed his son in history and literature, and entertained the children with vivid ghost-stories and tales of Edgar Allan Poe.Christian's positive behavior toward his children was overshadowed by his morbid pietism. Munch wrote, "My father was temperamentally nervous and obsessively religious—to the point of psychoneurosis. From him I inherited the seeds of madness. The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born." Christian reprimanded his children by telling them that their mother was looking down from heaven and grieving over their misbehavior. The oppressive religious milieu, plus Edvard's poor health and the vivid ghost stories, helped inspire macabre visions and nightmares in Edvard, who felt death constantly advancing on him. One of Munch's younger sisters was diagnosed with mental illness at an early age. Of the five siblings, only Andreas married, but he died a few months after the wedding. Munch would later write, "I inherited two of mankind's most frightful enemies—the heritage of consumption and insanity."

Christian Munch's military pay was very low, and his attempts at developing a private side practice failed, keeping his family in perennial poverty. They moved frequently from one sordid flat to another. Munch's early drawings and watercolors depicted these interiors, and the individual objects, such as medicine bottles and drawing implements, plus some landscapes. By his teens, art dominated Munch's interests. At thirteen, Munch had his first exposure to other artists at the newly formed Art Association, where he admired the work of the Norwegian landscape school. He returned to copy the paintings, and soon he began to paint in oils.

Studies and influences.

In 1881, Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design of Christiania, one of whose founders was his distant relative Jacob Munch. His teachers were sculptor Julius Middelthun and the naturalistic painter Christian Krohg. That year, Munch demonstrated his quick absorption of his figure training at the Academy in his first portraits, including one of his father and his first self-portrait. In 1883, Munch took part in his first public exhibition and shared a studio with other students. His full-length portrait of Karl Jensen-Hjell, a notorious bohemian-about-town, earned a critic's dismissive response: "It is impressionism carried to the extreme. It is a travesty of art." Munch's nude paintings from this period survive only in sketches, except for Standing Nude (1887), perhaps confiscated by his father.

During these early years in his career, Munch experimented with many styles, including Naturalism and Impressionism. Some early works are reminiscent of Manet. Many of these attempts brought him unfavorable criticism from the press and garnered him constant rebukes by his father, who nonetheless provided him with small sums for living expenses. At one point, however, Munch's father, perhaps swayed by the negative opinion of Munch's cousin Edvard Diriks (an established, traditional painter), destroyed at least one painting (likely a nude) and refused to advance any more money for art supplies.

Munch also received his father's ire for his relationship with Hans Jæger, the local nihilist who lived by the code "a passion to destroy is also a creative passion" and who advocated suicide as the ultimate way to freedom. Munch came under his malevolent, anti-establishment spell. "My ideas developed under the influence of the bohemians or rather under Hans Jæger. Many people have mistakenly claimed that my ideas were formed under the influence of Strindberg and the Germans…but that is wrong. They had already been formed by then." At that time, contrary to many of the other bohemians, Munch was still respectful of women, as well as reserved and well-mannered, but he began to give in to the binge drinking and brawling of his circle. He was unsettled by the sexual revolution going on at the time and by the independent women around him. He later turned cynical concerning sexual matters, expressed not only in his behavior and his art, but in his writings as well, an example being a long poem called The City of Free Love. Still dependent on his family for many of his meals, Munch's relationship with his father remained tense over concerns about his bohemian life.

After numerous experiments, Munch concluded that the Impressionist idiom did not allow sufficient expression. He found it superficial and too akin to scientific experimentation. He felt a need to go deeper and explore situations brimming with emotional content and expressive energy. Under Jæger's commandment that Munch should "write his life", meaning that Munch should explore his own emotional and psychological state, Munch began a period of reflection and self-examination, recording his thoughts in his "soul's diary". This deeper perspective helped move him to a new view of his art. He wrote that his painting The Sick Child (1886), based on his sister's death, was his first "soul painting", his first break from Impressionism. The painting received a negative response from critics and from his family, and caused another "violent outburst of moral indignation" from the community. Only his friend Christian Krohg defended him:

He paints, or rather regards, things in a way that is different from that of other artists. He sees only the essential, and that, naturally, is all he paints. For this reason Munch's pictures are as a rule "not complete", as people are so delighted to discover for themselves. Oh, yes, they are complete. His complete handiwork. Art is complete once the artist has really said everything that was on his mind, and this is precisely the advantage Munch has over painters of the other generation, that he really knows how to show us what he has felt, and what has gripped him, and to this he subordinates everything else.Munch continued to employ a variety of brushstroke technique and color palettes throughout the 1880s and early 1890s, as he struggled to define his style. His idiom continued to veer between naturalistic, as seen in Portrait of Hans Jæger, and impressionistic, as in Rue Lafayette. His Inger On the Beach (1889), which caused another storm of confusion and controversy, hints at the simplified forms, heavy outlines, sharp contrasts, and emotional content of his mature style to come. He began to carefully calculate his compositions to create tension and emotion. While stylistically influenced by the Post-Impressionists, what evolved was a subject matter which was symbolist in content, depicting a state of mind rather than an external reality. In 1889, Munch presented his first one-man show of nearly all his works to date. The recognition it received led to a two-year state scholarship to study in Paris under French painter Léon Bonnat.

Paris.

Munch arrived in Paris during the festivities of the Exposition Universelle (1889) and roomed with two fellow Norwegian artists. His picture, Morning (1884), was displayed at the Norwegian pavilion. He spent his mornings at Bonnat's busy studio (which included live female models) and afternoons at the exhibition, galleries, and museums (where students were to make copies). Munch recorded little enthusiasm for Bonnat's drawing lessons—"It tires and bores me—it's numbing"—but enjoyed the master's commentary during museum trips.